Oral History

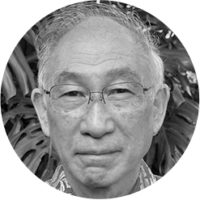

Oral History of Wing Tek Lum Session #1

Bamboo Ridge Oral History Project

Wing Tek Lum

Session #1

Summary

Interview of Wing Tek Lum (WTL), conducted by Ken Tokuno (KT) for the Bamboo Ridge Oral History Project via Zoom, on August 19, 2022. Wing Tek speaks about his education, his involvement in the emerging Asian American movement, the 1978 Talk Story conference, the Hawai‘i Literary Arts Council, his writing process and what influences his poetry, his time at Bamboo Ridge, and what he considers the four phases of Bamboo Ridge. Wing Tek also recalls Stephen Sumida, Marie Hara, Eric Chock, Darrell H. Y. Lum, and others.

Preface

The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Wing Tek Lum (WTL) on August 19, 2022. The interview took place via Zoom, and was conducted by Ken Tokuno (KT) for the Bamboo Ridge Oral History Project. This interview is the first of two sessions.

Wing Tek Lum and Ken Tokuno have reviewed the transcript. Their corrections and emendations appear below in brackets with initials. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Bamboo Ridge Oral History Project. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose.

KT: We are interviewing Wing Tek Lum for the oral history project for Bamboo Ridge Press and although I’ve already said his name, I’m going to ask him the first question, which is, please give me your full name.

WTL: Wing Tek Lum.

KT: And please tell us when and where you were born.

WTL: I was born in Honolulu in 1946.

KT: What was life like for you growing up? Anything you especially remember?

WTL: Oh, I think I lived a privileged life. I grew up in Mānoa. I went to Punahou and also went to college at Brown University and then I got a master’s degree in Divinity at Union Theological Seminary. I think one other thing that is important was that I have a very supportive family.

Unfortunately, my mother, who was a very devout Christian, she died when I was sixteen. That was a little bit more unusual than a lot of other contemporaries of mine.

KT: Can you think of anything about going to school at Punahou that might have affected your later literary career or interests?

WTL: Yes, and I want to start off with an anecdote about a party that I attended with a number of fellow writers where one of them asked around the table what was the favorite book or book series that you read as a kid. And again, these are all, you know, well-known local writers, and everybody went around in turn telling us who their favorite writer was. And, for instance, I remember Cathy Song said that the Madeline series was very influential for her. She really read all of the books in that series. When it came to me, I was at a loss as to what to say, how to answer it, because I have no memories, or shall we say no fond memories of reading or wanting to read a lot of books. I did okay in school, and I always had this feeling of inferiority that I just had to really work hard to finish the required reading list that we had in, you know, like third grade or fourth grade, so I never really felt that I was much involved with literature. On the other hand, I was really, really good in math and science, and that carried over to when I was in high school, and I, you know, took various advanced placement courses, and what not. I got into a good college because of my math and science record.

There is another anecdote that I can share that in high school for English literature we did have a class analyzing contemporary poetry and I remember class discussions on some Auden poems or Richard Wilbur poems, and I really liked them. But upon reflection I think that was because they were led by our teacher for close readings of the poems. And I thought, there are all these little clues that are in this line of the poem, or with that word and it was like solving a math problem. That’s the way I looked at it, so that was an interesting memory that I have, a fond memory that I have having to do with literature. But most of the time I was just, you know, I think that literature was not my forte.

KT: Why did you actually attend Brown University?

WTL: I went to Brown because my brother, my elder brother, went to Brown. He’s about ten years older than me and he went there. I applied there, and I got in, so that’s what happened and as I said I did major in Engineering because they figured out that I was good in math and science, so they put me in the Engineering program. However, I did take a five-year program, so that I graduated with a combined Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science degree. I minored in art and took some studio art courses. Also, I blossomed in college by experimenting with other things, and I got involved in poetry. I liked to read the Imagist poets like William Carlos Williams and others, and that really turned me on. And so one of my side activities was on my own just writing poems. I took one course creative writing and after that a second one, but that’s the extent of my formal education in creative writing.

KT: Did you pursue anything in engineering after you graduated?

WTL: No.

KT: So you went into something else.

WTL: Because also at that time, which was in the mid- and late-1960s the country was involved in the Vietnam war. There were a lot of civil rights activities, so as another extracurricular involvement, I also was involved in anti-war activities, in civil rights and in some social work. And I also ended up being, in my last year, the editor for our literary magazine. Actually, there weren’t that many people writing at my school, so maybe I got that position by default.

KT: Were you publishing any poetry back in those days?

WTL: Just in the literary magazine. And again, I wasn’t that good, you know. I didn’t really take many formal courses. I don’t have that kind of a foundation in taking Shakespeare courses, or novels, or whatever that you would have had to have taken if you graduated with a degree in English. I think all of this was a lot of different experiments during my five years in college, and I was doing a lot of different things not only in the academic area. I’m grateful that I went to this particular school that allowed me to do other things besides just focusing on engineering courses.

KT: And so after that we know you attended the Union Theological Seminary. What were you planning to do with that, with that experience?

WTL: I wasn’t really sure. As I said, my mother was a very devout Christian, so I had some basic values which I received from her. I also had a lot of existential questions that I tried to deal with while I was in college. I mean again, the war, social injustice with the civil rights movement. Things like that and so I talked to the chaplains in my college and they said maybe one possibility was to go to a seminary to figure these questions out. And again I am grateful that I did so that I could figure out more about the questions that I had: race, life and death, etc. I did study Bible and church history. Those are some of the standard courses. But this particular seminary allowed me to study—well, they were encouraging me to get involved in other activities outside of the school. And I lived in New York, in Chinatown. The Union Theological Seminary is located in New York City, across the street from Columbia University. I lived in Chinatown which is in the Lower East Side and I had a job working in a social service agency in Chinatown. And this was from 1969 to 1973.

I was working half-time and going to school half-time. The school again allowed me to grapple with some of my identity questions. So, I got credit for going to Columbia to learn Mandarin without having to learn Greek or Hebrew, which other people in the seminary did. Because they were encouraging me in my interest in helping people in Chinatown. I was grateful for, again for this particular seminary, just like at Brown, having a more liberal curriculum that allowed students like me to experiment and learn about different things other than simply the traditional standard course work. This is important, because at that time in the late 1960s and 1970s, this was the very beginning of what is now considered the Asian American movement.

This was not only in literature, but also all kinds of other areas like education and social services. And especially for me I was connected with a social service organization in New York Chinatown that helped immigrants in Chinatown. This was after the 1965 change in the immigration law [abolishment of the national origins quota -Ed.]. So I arrived very shortly after that time that there was large influx of immigrants to New York City, including in Chinatown. The community there was changing. I was there sort of on the ground floor of that change. This Chinese American movement started primarily in San Francisco and then moved to the East Coast. And at that time I realized that because I didn’t really speak Chinese, I was limited in how I was able to help people with any real problems. After I graduated from seminary, which was in 1973, I was in Hong Kong for three years learning Cantonese in a school but also doing social work half-time. So all this time, from 1967 on, while I was at Brown and all this time through living in New York, and then, also then living in Hong Kong, I was also writing poems. I’ve kept writing and, luckily, I was able to be published in some of the early Asian American literary journals because there weren’t that many people around. This included the Aiiieeeee! books but I’m also in some of the other anthologies that were published in the 1970s. That’s because I tried to observe what I was doing in New York City, and then later in Hong Kong, and write some of those observations down as poetry.

KT: How long were you in Hong Kong?

WTL: Nineteen seventy-three to nineteen seventy-six. Three years.

KT: And you’re mostly doing social work.

WTL: Going to school and working. Then in 1976 I moved back to join my family business that is in real estate here in Chinatown in Honolulu. I kind of, you know, I was trying to figure out, trying to learn the lay of the land as far as the literary scene here in Honolulu and the next year, 1977, Marie Hara luckily approached me and said that she and Stephen Sumida and Arnold Hiura were organizing the Talk Story conference in 1978. She wanted to know if I would be interested in participating. Marie’s brother-in-law was my good friend in third grade, and so we had this connection. I knew of her husband, John. And so that was the entree to meeting Marie. That is how I got exposed to local literature, through the efforts of Stephen, Arnold, and Marie to organize Talk Story. I would want to say especially that I wasn’t an organizer in the Talk Story conference. I was a participant. I was somebody who was invited to participate. The hard work was actually done by those three and others like Eric Chock, Gail Harada, and others. I was just there to participate.

KT: Could you speak more about the Talk Story conference in terms of what was their goal and what was the conference like?

WTL: You first have to understand the situation in the literary world in Hawai‘i at that time in the mid-’70s, which was basically dominated, just like the plantations, by certain arbiters at the University of Hawai‘i. There was the famous [A Hawaiian Reader] book that came out that was compiled by James Michener, A. Grove Day, and Carl Stroven. That was a top-down imposition of the literary canon, which was essentially a lot of haoles [including tourists], who came and made a lot of observations—and that was it.

You first have to understand the situation in the literary world in Hawai‘i at that time in the mid-’70s, which was basically dominated, just like the plantations, by certain arbiters at the University of Hawai‘i. There was the famous [A Hawaiian Reader] book that came out that was compiled by James Michener, A. Grove Day, and Carl Stroven. That was a top-down imposition of the literary canon, which was essentially a lot of haoles [including tourists], who came and made a lot of observations—and that was it.

KT: You mean going back to Robert Louis Stevenson and Herman Melville, people of that nature?

WTL: And James Michener and, of course, his idea of the Golden Man, where he promoted the idea that we would all assimilate into one big melting pot. There would be no distinct or unique ethnic groups. Just one big sameness. And of course the insidious part of this is that the melting pot actually makes it easier for these arbiters to declare what is the sole aesthetic for all of Hawai‘i. They get to determine what is good literature or bad, and everyone else must concur, since by definition we are all the same.

And this sameness ignores what was being written or had been written since the early 1900s in English, from ethnic writers in Hawai‘i like James Chun, Wai Chee Chun Yee, Li Ling Ai, Milton Murayama, and Kazuo Miyamoto—all of whom were people whom Steve and Arnold rediscovered when they did their annotated bibliography of Asian American literature in Hawai‘i. It was really a game changing bibliography. What they published was a counterweight to A Hawaiian Reader, the canon that was selected by Michener, Day, and Stroven. That was the setting for what was happening in the mid-1970s. When the three organizers decided to do Talk Story there was a lot of controversy. I think I mentioned in another speech that Marie Hara was at the UH English department at the time, and she was treated like, in her words, a rebel in the Empire [which is a “Star Wars” allusion]. She had a hard time in her department. She was a lowly lecturer or instructor and there were senior people in her department that were not happy that these organizers put forth this alternate point of view that other literatures were also valid.

Talk Story was a watershed event for a lot of people like me and others who were writing their own individual poems and short stories on their own, but not realizing that there were other people who shared some of the same concerns, and some of the same writing styles as themselves. The conference gave us a way to provide some kind of an alternate forum for a mass of ethnic writers. And we found a common ground through that conference and through the networking. It was basically talking story with fellow writers whom, at least for me, I didn’t know existed. I thought I was writing on my own without too much encouragement by anybody, and I found a community [of like-minded people]. That was very important, and their platform, their philosophy was not this sort of Golden Man or melting pot myth. But it was what Stephen wrote in a position paper about cultural and literary pluralism, where you can do your own thing, but within sort of a common area of understanding and we can communicate with each other by talking story. But that doesn’t mean that you have to do the same thing. You can be different and unique, and just because you’re right doesn’t mean that I’m wrong. It just means that I’m different. That’s a kind of cultural pluralism that I think was espoused by the Talk Story organizers and we bought into that particular notion as opposed to the melting pot, which was saying we all have to be aspiring, to be writing the same thing, that there is a single canon.

And we found a common ground through that conference and through the networking. It was basically talking story with fellow writers whom, at least for me, I didn’t know existed. I thought I was writing on my own without too much encouragement by anybody, and I found a community [of like-minded people].

Also, I’ve written elsewhere about different issues that came out of the conference, such as comparing the different points of view between mainland writers who attended the conference and local writers.

There were also distinctions within the local literary community, and there was this issue of assimilation and acculturation which has to do again with the melting pot myth and pluralism. There was a big controversy on Pidgin, which is in itself a language of talking story among different ethnic groups and linguistic groups. And there’s also this kind of understanding of generations, and how for me as a writer in the 1970s, I thought I was doing this on my own and inventing the wheel for the first time. And that’s not true because there were generations before us that were writing and there’s a literary history. So, all of this stuff came up in Talk Story that at least I got from participating and attending the readings and listening to other people share their stories and their poetry.

There was a big controversy on Pidgin, which is in itself a language of talking story among different ethnic groups and linguistic groups. And there’s also this kind of understanding of generations, and how for me as a writer in the 1970s, I thought I was doing this on my own and inventing the wheel for the first time. And that’s not true because there were generations before us that were writing and there’s a literary history. So, all of this stuff came up in Talk Story that at least I got from participating and attending the readings and listening to other people share their stories and their poetry.

Those were some of the issues we were dealing with in that conference, but then let me go further. Historically, for me, there are certain major consequences in the aftermath of that 1978 event. One was, as I said before, that Stephen Sumida and Arnold Hiura published this annotated bibliography. All that they could find in all of the libraries and elsewhere in Hawai‘i about ethnic writing, local literature written in English from the early 1900s onward. Another achievement was a little bit later. The bibliography was a catalyst for Stephen Sumida to go back to complete his PhD work. He later published his thesis, “And the View from the Shore,” which was a milestone of literary criticism of local literature. Also, in 1979, Frank Chin’s visit. Frank did not participate in the Talk Story conference. We brought him over in 1979, and he was the primary writer of the Aiiieeeee! collections that were published on the West Coast

KT: Can I stop you there for a second and have you talk a little bit more about Frank Chin and Aiiieeeee!? I remember Aiiieeeee! myself, but most people probably aren’t familiar with it.

WTL: Well, I mean it was one of many. There were other books that tried to anthologize poetry and short stories written by Asian Americans. This was during the mid-1970s. Frank, along with his fellow editors Jeff Chan, Shawn Wong, and Lawson Inada—their collection probably stands out head and shoulders over the rest and they were able to re-discover a lot of people who had written during the previous generations, but then were forgotten about. And again the task was to show that there has been a literature that was written prior to the 1970s and that can serve as a foundation for our literary history. For instance, they re-discovered “No No, Boy,” by John Okada and Louis Chu’s “Eat a Bowl of Tea.”

KT: But their perspective was predominantly mainland American, right?

WTL: Yes, but I think we shared a lot of that same perspective. Obviously, there were some unique local circumstances that were different from what was happening on the mainland, but you know they had the same kinds of problems. The American literary establishment on the mainland looked at Asian American writing as a sort of a second-class literature, and wanted to maintain their literary dominance as sole arbiters. The Aiiieeeee! editors were trying to present a different point of view that said we have our own literature. They were trying to point out things like self-hatred internalized by minorities trying to cater to the white establishment. Their perspective, to me, provided a counterweight again to the demeaning perception of Asian American writing at that time.

KT: Thank you. Do you want to say more about that, or—

WTL: I want to just say a few more things about the consequences of the Talk Story conference. Okay?

KT: Great? Yes.

WTL: Besides Frank Chin coming in 1979, in 1980 some of us decided that we wanted to have our fair share of the, getting involved in the literary establishment in Hawai‘i. You know there was the Hawai‘i Literary Arts Council, which had a fair amount of money at that time, that the State government gave to the organization to promote readings. It was being used especially by UH professors who wanted to bring in their own friends to give readings [providing in return a paid vacation to Hawai‘i]. So we thought, let’s try to get our fair share. In 1980, there was an election and we took over the organization. Eric Chock was president and I was treasurer. This led to us to being able to have funding to invite Asian American writers that we heard about on the mainland to come to Hawai‘i to give readings, so we were exposed to and learned from writers like Laurence Yep, Jessica Hagedorn, Wakako Yamauchi, Li-Young Lee, David Mura. We were able to invite people paid for by the Hawai‘i Literary Arts Council, which had received funding from the State. So those were some of the consequences of Talk Story. Over the next several years not only did it inspire Eric and Darrell to create Bamboo Ridge at that time, but there were these other related events that occurred that in concert helped to develop and evolve local literature. It was kind of neat that we, that we were able to do this.

KT: Great. Well, of course, we want to get heavily into your involvement with Bamboo Ridge in the early days. But can I step back from it and ask you again what were major influences in your own poetry writing of either local writers or mainland writers or past writers who might influence you? Chinese American or Chinese or anyone?

WTL: There were several. I already mentioned the Imagist poets like Williams and that has always been important for me. I’d like to back-track a little bit to also say that I’m a slow reader and a slow writer, from elementary school on. My idea is that I am wired differently from my good friends who are local writers who write in prose. They are able to read documents or books very quickly and they also can write very quickly. They can write whole paragraphs where I agonize over one or two words. I would say that that’s diarrhea of the mouth, instead of constipation.

As an example, especially in the early years, I liked to look at photographs and then write about a photograph. What I mean by that is that I look at it and see some details, and then I put them down on paper and go back to look at the photograph and look at some more details and put them down, so I tried to evoke in words what I saw in the image. That using a photograph is telling because it’s like a slice of time. Whereas I think again, for prose writers, they are more interested in how different slices or points in time interact and relate to each other. More like a movie, rather than a photograph, and that’s because they are interested in the changes that result. So in their writing they have a beginning, a middle, and an end, which is a plot. But for me, because I think I’m wired differently I just stop at this one single moment and I try to concentrate on that. Moreover, what I learned early on was to try to show rather than tell. And what I’m told is when you go to creative writing courses, they tell you: Don’t tell. Don’t say you know the sun is hot. Instead you show it by describing about how people are sweating and their skin clings to the back of their shirt, all that kind of stuff, because they’re wearing too much clothes. So that whole idea of showing instead of telling and writing a lot of details so that I am concentrated on a moment in time is, I guess, what I feel is my strength.

My weakness is trying to move it along and come up with something like a plot, which is the stuff that my fellow prose writer friends are more into. That’s kind of my writing style. I also want to add to that. I think what I developed over time was, and what was nurtured by living in Hawai‘i was, a couple of things. One, a focus on family and I’m talking about trying to reflect on my first published collection, Expounding the Doubtful Points [Issue #34/35 -Ed.]. So, there’s a focus on family, about my parents and grandparents, and also about my daughter. For me, the notion of time is expansive. It’s generational. That I am living here today, but I am also a part of people who have come before me, historically speaking. They course through my veins; they still live through me. Another notion is place, the idea of place, which is because we live on an island; geographically we’re limited to, restricted as far as moving around in long distances. And so, you know, there’s this whole joke about everybody asking what high school you went to, and who you are related to, don’t talk stink because you might be related to somebody. You know, that kind of stuff is important because we live on an island, a small community, that kind of thing. Place is actually restricted or circumscribed. Those kinds of things, I think, bear on the writings that, at least, I was involved with, so one of the consequences of this is that we have learned that we need to communicate clearly. For me that means clear images, not obscure allusions, which you know are some inside joke for one or two people. I try to convey to other people in a clear way what I believe is important in the poem and trying to do it in a way that shows, not just tells.

I also think that there is this narrative sense which we value. It’s more linear than the nonlinear writing that was prevalent, that was popular then and is still popular now. There’s a sense of trying to communicate with other people. I don’t write in Pidgin. But that’s also a reason why other people do write in a pidgin: to try to communicate in this common language that has been developed in Hawai‘i. That’s trying to answer your question about my writing voice. But I think it also gives a sense of what I saw and felt in common with other writers who joined Bamboo Ridge; that they had some of the same kinds of voices. They’re trying to find common ground. That’s trying to answer that question of people’s voices, personally my voice, but also trying to say why I thought I felt comfortable in joining Bamboo Ridge. There are other people who were writing some of the same concerns, content-wise, issue-wise. The voices were similar enough that I could understand and communicate.

KT: So it’s interesting that you use photographs to write some of your poetry, which you’re kind of taking, you’re kind of translating a visual image into a verbal image. But I’m sure you’re trying to add something else that’s beyond the actual content of the photograph.

WTL: Correct. That’s the editorial voice I have. You have a didactic motive which I’m sure is evident in a lot of poetry. I mean that’s like going from even the very beginning of my writing. There’s this poem that I wrote in 1971, one of the best poems that I have ever written, entitled “A Picture of My Mother’s Family,” which is in Expounding the Doubtful Points. A very long poem. It is just looking at the picture that was taken of her and her parents and siblings around 1915. And all of them except one aunt had died by 1971, and so I tried to add some of the few things I knew about their lives and their deaths. This is a poem that is about a photograph that stopped time in 1915. By my writing about this particular photograph, I in turn try to resurrect my ancestors. That is of course impossible, and so there is the sadness surrounding this impossibility. That is the didactic intent of this poem though I try not to make that specific, but let the reader come to that conclusion by himself or herself.

KT: I’m going to interrupt you for a moment to make a brief commercial message from Bamboo Ridge because you’ve mentioned Expounding the Doubtful Points and I just wanted to say that that is one of the more popular books that is available on the website where we have preserved digital copies of the older books that Bamboo Ridge has published and anyone can log into that site and read Expounding the Doubtful Points for free.

Thank you. If you don’t mind, can we go on to Bamboo Ridge itself? How did you first learn about it and how did you first meet Darrell and Eric?

WTL: It was through Talk Story. You know Darrell and Eric were involved in the organizing of the conference. And I got wind of their efforts to start the literary magazine. Then during that conference Eric released Bamboo Ridge’s first book, which was his chapbook Ten Thousand Wishes [and I still have my autographed copy of it that I proudly have saved -WTL]. Again, they did that on their own, without my involvement, because, as I have said many times over the years, if they had asked me about it, I would have told them that it wouldn’t pencil out. It would be a big money loser and that is actually still the case. They haven’t learned, we haven’t learned that in all these almost forty-five years. And they just disregarded that. I’m sure that they thought they might make some money, but they disregarded people who were more rational. And so as the dreamers that they were, they did persevere. They started Bamboo Ridge on a dream. So, Talk Story was in the summer of 1978. Eric’s book came out during Talk Story and then they started soliciting and then ultimately published the first issue in December of that year. So, they did it all on their own. Other people helped them out and encouraged them. I was not one of them, because as I said I thought it was a pipe dream. I believe I did attend the first reading, but just as a member of the audience. So, that’s what happened in the beginning and they did all the work from soup-to-nuts. Not only the editing and the soliciting of writers’ materials from local writers who were in the first issue. They also did all the production work, the distribution work, everything. They fronted the money. So, you know, hats off to them.

KT: Yeah. So how did you get involved in doing more than writing for Bamboo Ridge?

WTL: That was, I think, in Issue #5. I liked what they’re doing and I said, well, you know, do you need any help? And they said, well, maybe in the area of proofreading. So, in Issue #5, they let me go to Darrell’s home, which was in Kalihi and they had gotten all of the works typeset on this big roll and they were cutting all the pages up and putting them onto these boards with wax. My task was to compare the author’s original submission with what had been typeset and laid out on the board. And the typesetter was Alice Matsumoto of Creative Impressions, and if she made a mistake, you know, as the proofreader I would correct it. And then I think Darrell has mentioned that if we discovered that an error had been made we needed to hunt around in the pile of discarded pieces of typesetting and make a replacement. So, if a comma was missing, or some word, we would have to go through the discards to retrieve a comma, cut it out, and then paste it in as an insert on the final version on the boards. My task was to help them out, was to help them with the proofreading while they were cutting up the work and pasting it on the boards. Of course, there were some complications with my job, because I always suggested that maybe we should try to look at original manuscripts and copy edit them before we send them to Alice for typesetting, so we can clean them up grammatically and all that. And they did try to do that, but I do remember there are several instances where I would discover something from the original author’s submission, the manuscript, that didn’t match when comparing it to what was typeset and already put on the board. This would create some humbug, which would create some backtracking to fix the error on the boards.

And then there is an infamous instance where I was not given the original manuscript, but just had to go over what had been typeset on the boards. And I believe Alice had made a typesetting mistake on one word in a poem, but no one had made a comparison check with the manuscript. So the error found its way to the published version, which ticked off this poet who was already pretty ornery. He knew I was the proofreader and so I got hell from him for a while, even though it was not my fault. Anyway he got over it later on, and we returned to being friends. [I gave a eulogy for him at his funeral. -WTL].

I think the most exciting one that I did in that regard is Issue #23, which is Chan Is Missing. Chan Is Missing is from Wayne Wang’s movie, which he allowed us to transcribe and publish. Diane Mark did the transcription for the English part of the movie. I did the transcribing for the Chinese parts and we got a Japanese printer here to typeset the Chinese characters. So that was a big challenge because when we were laying the stuff on the boards and then if there were any changes in the Chinese parts, we’d have to stop and go back to the Japanese printer to print out the typeset of the Chinese corrections and then lay them on the boards. So that was one of the more unusual experiences as far as my getting involved in the proofreading.

Anyway, these production nights were basically Eric and Darrell, with sometimes me helping with proofreading while they were waxing the typeset on the boards. That was the last step to get the issue camera ready for the printers. I don’t remember though when I stopped being a proofreader. One last memory of proofreading is that I didn’t get paid for this task as I was a volunteer. But I still have saved a note from Darrell notifying me that I was being issued a complimentary subscription for my proofreading services.

I also got involved in mail orders. Subscriptions were a different story, and so was the distribution to bookstores or Longs Drugs. But if an individual ordered a book, we had to take it out of the inventory and mail the book to that person. Originally that had been done by Eric and Darrell, but they needed help in that area, so I helped them out with doing mail orders. This meant stuffing individual books in mailing pouches and putting stamps on. So, I had to keep on hand not only a small inventory of the various books, but mailing pouches, labels, stamps, the rubber stamp for our return address, etc.

They had a delivery person as well for distribution and that was initially Stacy Tsuji, who was Darrell’s nephew, and then we also had for a long period of time Ed Nartatez who was a student at the KCC Culinary Institute. He had his own separate inventory that he kept in his house and we’d tell him about deliveries of books to either a bookstore or the post office.

I had at some point in time gotten the bulk of the inventory originally held by Eric and Darrell, and I’ve kept that bulk of the inventory in my office basement ever since. I don’t remember exactly when but I think it was again probably in the mid-1980s when I became warehouse manager so that was pretty early. Included in what Eric and Darrell gave me were the earliest issues which they had saved. So these went into an archive, again in my basement, for safekeeping. This was for books starting with Eric’s chapbook, but then also going forward we decided to put aside ten copies of each of the new publications. So I am responsible for continuing to maintain this archive.

KT: Do you want to say something about other people who may no longer be with us, that were important contributors to Bamboo Ridge in the early days?

WTL: I’ve mentioned people like Ed Nartatez for delivery. We also had other mail order clerks like Cathy Song, and then her mother Ella. Until she died, she helped out with our deliveries and mail orders [she was the one who got paid, though her husband actually drove the car and took her to lunch -WTL]. These are people who were involved in the distribution part of Bamboo Ridge, not in the editorial part.

We also had several volunteers for events. People like Marie Hara, Gail Harada, Mavis Hara, and others helped at readings, book sales, fundraisers, anything that involved public events. That’s when we needed more people to help out. And I should mention that Marie was always around as someone whom we could consult with; to me she was like an elder sister for the press.

Eric and Darrell did the bulk of the editorial work which involves soliciting people to submit poems and short stories, but also making the selections. And also deciding if we should publish a single author collection or a collection on a single theme. They also did the grant writing for many decades [Eric for public grants and Darrell for private grants], and Darrell especially was involved in the production area. But to coordinate all of that, I think, starting with around Issue #13 or #14, Dennis Kawaharada was the first managing editor, who started to help out more with management duties of the press or like what the publisher of a press does. He didn’t get directly involved in editorial work, but he got involved in coordinating everybody else. And so Dennis was our first managing editor which also included being bookkeeper and he was around until around Issue #31/32, The Best of Bamboo Ridge, and then he fell in love and moved to the mainland. He got his PhD on the mainland and I took over the bookkeeping from Dennis. There are other people who continued as managing editor like Tino Ramirez, Mavis Hara, Gail Harada and Cathy Song, and then ultimately Joy Kobayashi-Cintrón. So those are some of the key people who were involved in trying to help with the back office.

I’ve been asked whether I ever wanted to be an editor. Darrell and Eric invited to me to be a guest editor for some issues and I always said no because I didn’t really like that responsibility, you know. This thumbs up and thumbs down part that, you know, you can play God. I guess, I just thought it was too much work and you have to read all of these manuscripts and make hard decisions. Sometimes you have to reject people and tell them that this work was not that great or didn’t fit. Eric and Darrell maybe didn’t like to do this either, but I think that overall they knew that that was part of the responsibility of trying to shape or develop an aesthetic which has then lasted for decades. But I never thought that was part of my strength so I’m part of the team that worked around Eric and Darrell and enabled them to publish their work and make known their aesthetic that they developed over time. My contribution to Bamboo Ridge is as an enabler. Just like all of the other guys who have been involved, enabled Eric and Darrell to do what they knew best: the editorial work. And it was a cooperative effort, an effort of trust in each other that we had. They were working on developing an aesthetic, developing a voice for the press. That’s where I see my role in Bamboo Ridge is.

My contribution to Bamboo Ridge is as an enabler. Just like all of the other guys who have been involved, enabled Eric and Darrell to do what they knew best: the editorial work. And it was a cooperative effort, an effort of trust in each other that we had. They were working on developing an aesthetic, developing a voice for the press.

KT: I have no more questions. but is there anything else you want to add that I haven’t asked or do you think it’s important to talk about?

WTL: You asked about major influences in my own writing. I neglected to mention Chinese writers. That’s also what I learned from living in Hong Kong. I was able to read a lot of books that I acquired in the bookstores there that were translations of the ancient Chinese poets in English. One of them was T’ao Ch’ien whom I’ve spoken about at our preservation celebration this past March. Very important for me as he was asking existential questions which I was also personally dealing with at the time and writing in a style I’ve tried to emulate. But then, later on, I was also influenced by other Chinese poets like Tu Fu and Wang Wei. And so those guys have been writers that I go back to reading over and over; they continue to be a major inspiration for me.

I also wanted to add something from my prepared notes about Eric and Darrell working together. In my observations, they were complementing each other. I mean they have their own individual strengths—not only the most obvious one which is that Eric writes poetry and Darrell writes prose and drama. Eric worked with Poets in the Schools. He was working with little kids and trying to encourage them to write and also dealing with the State Foundation for Culture and the Arts which funded that particular program. So, he had that background that was helpful in his own poetry but also in his grant writing. Darrell working with Special Student Services at UH was working with counseling college students. He also had an interest in education and ultimately got a doctorate in Education. He’s also, has done a lot of work in art, and the covers of the first issues were his artwork. So, he got more involved in production. And so, the go-to guy for production was Darrell, not Eric. They had their strengths and complemented each other in the beginning years. My observation is they overlapped, but they had their own strengths, and so they were able to cover all of the bases starting a periodical. But then when it got bigger and bigger, they needed help. And so people like Dennis Kawaharada stepped in as manager.

I helped out in some ways, and there are others like Gail Harada, who stepped in and did a lot of different things like she was managing editor for a while. She was also grant writer for a while. She also had worked with Eric at Poets in the Schools. People that were able to step in over time when Bamboo Ridge got larger and larger enabled Eric and Darrell to continue to concentrate on the thing that they did the best, which was to develop this aesthetic for what was going to be published in the magazine.

I can add another thing. Eric’s book of poetry came out in the summer of 1978, but officially the first issue came out in December 1978 and they gave it a number, #1. I’ve written elsewhere that this was a commitment by Eric and Darrell to say we’re not going to be just an occasional press to publish books whenever we want to. The implication is also we can close up shop whenever we want to. No, we’re going to make a commitment to you, our readers, that we’re going to continue to publish for a long period of time. There’s going to be an Issue #2, Issue #3, Issue #4. So this commitment or promise is something that we will make if you will buy a subscription. So there was a contract between the publishers of Bamboo Ridge and its subscribers. It was also a contract with its authors, that the authors would continue to submit work that would provide the sustenance for the press to publish.

Then the press evolved over time from being just a regular literary journal, an anthology each quarter. It evolved because after a while there were people who had amassed enough material for a collection of short stories or poems, or whatever. And they would say I have enough for a book. Can you publish my entire collection of short stories? And eventually we got into the habit of interspersing what we call the regular issues, the journals, with single author books and then, later on, also single-themed books, like Bamboo Shoots [Issue #14 -Ed.], or Pake [Issue #42/43 -Ed.], or Malama [Issue #29 -Ed.], etc. The press has continued to evolve over these almost forty-five years, but we have kept our issue numbers, so that now we are up to #121 and #122 this year. I think that’s keeping the promise that Eric and Darrell established with Issue #1, that commitment that they had as a contract to subscribers and to the authors.

One last thing. Some people get confused as to whether we are a literary periodical or a publisher of one-off books. We are actually both, and I think this commitment to do both makes Bamboo Ridge unique. From the beginning, Eric and Darrell wanted to publish what was being written on a current basis. That was like taking the pulse of what was happening in local literature at a specific time, and that could only be done via a periodical, featuring works by the many voices that make up local literature. However, there were other times when it was good to take a step back and collect someone’s group of poems, or assemble an anthology of works on a single theme [like Pake which came out during the bicentennial celebration of the 200th anniversary of the arrival of Chinese to Hawai‘i, or Intersecting Circles which was a collection of hapa women writers -WTL]. It was a summing up that allowed for more of a longer-term overview of someone’s writings or some particular issue. So we tried to do both—though admittedly that has confused some readers who want to pigeonhole us into one thing or another.

KT: Well, you referenced the idea that it was originally a quarterly journal, and we know that it’s not quarterly anymore. Do you remember why they decided to cut back on the number of issues per year at that time?

WTL: It was a lot of work to come out with it so frequently. It was a lot of work, because, yes, there may be the same amount of material being published in two single issues versus a double issue. But the other work, which is the production work, is reduced in publishing double issues [though maybe not in half -WTL]. Plus the distribution effort is reduced. The promotion work is reduced, so I think it got to the point where we decided it made sense for us to not continue with always doing single issues. I think, the first double issue was Best of Bamboo Ridge, Issue #31/32, and then followed by a regular issue, #33, but then my book Expounding the Doubtful Points was a double issue, #34/35. We then started doing single-theme or single author books that were considered double issues, but the regular issues were still single-numbered issues. What that meant was, we still provided the subscriber with four issues: a regular issue and a double issue, and then followed by a regular issue. They got three physical books but it was counted as four. Later on, it got even more challenging so we started just publishing two books a year, numbering each one as a double issue. Eventually later on when we were doing Issue #67/68, we said this is kind of stupid so let’s do Issue #69 as a single numbered issue. And from then on up to this year, with Issues #121 and #122, they’re all single numbered issues. As a subscriber you get two issues per year, that’s it, instead of in the beginning you got four issues on a quarterly basis. So it’s a kind of an evolution based on distribution and production.

KT: Well, I thank you. I think we can wrap this up unless we have any final things you want to say.

Wing Tek Lum is a Honolulu businessman and poet. Bamboo Ridge Press has published two earlier collections of his poetry: Expounding the Doubtful Points (1987) and The Nanjing Massacre: Poems (2012). With Makoto Ōoka, Joseph Stanton, and Jean Yamasaki Toyama, he participated in a collaborative work of linked verse, which was published as What the Kite Thinks by Summer Session, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa in 1994.

Ken Tokuno has contributed poetry and short stories to the pages of Bamboo Ridge and first started volunteering after he retired from the University of Hawaiʻi in 2017.

“I was always a great admirer of Bamboo Ridge and thought it would be a great idea to develop an oral history by talking to the people who were instrumental in its creation and success. Talking to Wing Tek Lum was a special experience for me since he has been a major figure for the Press for so long, plus he’s a great poet.”

Talk story