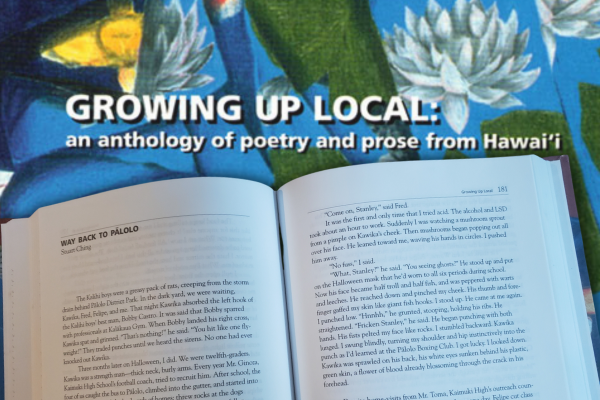

Growing Up Local (Issue #72) is one of our most popular books. HONOLULU Magazine named it one of “50 Essential Hawai‘i Books You Should Read in Your Lifetime” and it’s still used in classrooms today, twenty-five years later. Edited by a dream team of writer-educators including Eric Chock, Jim Harstad, Darrell H. Y. Lum, and Bill Teter, it’s a selection of stories and poems that have become Hawaiʻi favorites. One of these short stories, “Way Back to Pālolo” by Stuart Ching, is the inspiration and basis of a new movie, also titled Growing Up Local, by filmmaker James Sereno.

In this exclusive interview, we ask Stuart and James some casual questions on their recent collaboration in turning a local short story into a screenplay and film. They share insights into the process of adaptation and reflect on the challenges and rewards of working to bring local narratives to life on the big screen.

What inspired you to choose this particular short story for adaptation into a film?

James: I grew up in Kapahulu and was living in Pālolo when I first came across the story. I truly connected with the characters and loved the story and setting. I felt it would make an amazing film.

What were some of the key steps involved in the adaptation process from short story to screenplay, and how did the story’s core message and themes remain intact during this transformation?

Stuart: I didn’t really think about preserving the story’s core messages and themes. For me, the process was about trust and chemistry—and then letting go. At the outset of the project, to gain permission to option the story, James shared with me some of his local commercials and one of his award-winning short films. After viewing those, I knew that I could trust him with the story, so I released the media rights to his company while retaining the literary rights. Then I let the creative process run its own course and gave James the creative freedom that he needed to tell and shape and rewrite the story in a different medium/genre, and in the way that he wanted to.

How did you decide what to keep from the original story and what to change? What were the biggest challenges you faced during the adaptation process?

Stuart: Deciding on the story’s content for the initial version was not so much a strategic choice for me. The content was more driven by storytelling intuitions from both of us, I think.

On my part, I had already published several Pālolo Valley stories (with both shared and different characters), and the central elements of the core story, along with elements of two other stories and parts of a few unpublished drafts set in Pālolo Valley, found their way into the fictive universe of the initial film treatment and the early versions of the screenplay. For me, these elements were already swirling in that imaginative space, so they emerged naturally during the early writing.

For me, the artistic process was also more fun than challenging. I entered the project with no expectations. I was just grateful that an opportunity to try something new had just fallen into my lap. Because I had no expectations, I enjoyed the creation and revision and learning processes fully.

What was the collaboration process like, writing the screenplay together? What was it like doing rewrites on set (if there were any)?

James: Actually, it was interesting. Stuart had never written a screenplay before and when we first talked about expanding the story, Stuart wrote the entire thing out like it was a novel. Then I took that and adapted it for a screenplay. When he saw his words in a new form, he was able to see it clearly and we went from there. We began this process over 15 years ago and when I picked up the story again a few years ago and decided to rewrite it and shift the story to Nalo, I needed to get Stuart’s blessing to run with it on my own. Stuart was cool with it and had a lot of ideas and shifts that were helpful for me. Stuart wasn’t there on set, but was very involved with watching the different edited versions of the movie and sharing his thoughts on the different version. It was a true collaboration.

How did the original story influence the visual aesthetics or overall atmosphere of the film?

James: There is a feel to Pālolo, which is similar to Nalo. Both places are self contained and truly have one path to get in and out of. My girlfriend lived in Nalo so it was a natural shift for me as I was already there and knew both places well. We filmed in her family home, her home and her aunty’s home. Not for cost reasons, but because I wanted it to feel authentic to me and now her, to play right. In the film, the grandfather’s name is Masato Nagata. This is her grandfather’s first name “Masao” and my grandfather’s last name “Nagata,” my moms maiden name. Just made sense to me.

In what ways did you incorporate and celebrate aspects of Hawaiian and local culture within the film to create an authentic representation of the setting and characters?

James: There are two timelines in the story. One follows the grandson Stanley in the present day narrative, which is actually set in 1992. The other narrative follows the grandfather thru the history of not only his life but the story of Hawaiʻi. The plantation days, WW2, Statehood. All of these moments play a part in the story and shape Stanley’s journey.

How is writing a short story and writing a screenplay different or the same?

Stuart: Fiction writing relies heavily on descriptive language. We paint scenes and emotions and moods and dramatic situations and even conversations through descriptions and spatial arrangements created through language. We also have to master point of view and narrative distance—especially for third-person limited omniscient stories—when the fictive author (persona) expands and narrows the narrative distance in relation to the character and often moves seamlessly in and out of the character’s consciousness. In contrast, screenplays are written sparely. They rely much more heavily on dialogue, and filmic visual content, and music.I also learned from James that a film needs a tight “spine”—in other words, a tightly connected plot. And learning that filmic concept deepened my understanding of fiction writing more broadly.

Today I teach fiction and creative non-fiction writing in college, and that added understanding of fictive plot informs and enriches the feedback that I give to my students when we confer about their works-in-progress and when they are struggling to find the main thread of their story.

In what ways do you feel telling and preserving local stories is your kuleana and why is it important?

Stuart: When I was a student at UH in the 80’s, I was initially a P.E. major. I was planning to teach P.E. and coach football and powerlifting. Then I took an advanced writing course and an introductory creative writing course that were life-changing. For the first time in my life, my teachers invited me to tell stories of my life—and even in Pidgin! I had always imagined a writer as someone else, never someone in my image. But through those courses and the encouragement of those professors, I realized that my stories held value.

Growing up in the islands and speaking the local Creole, I never imagined myself as a writer. All the more, I think it’s important for all young people in Hawaiʻi to know that they have stories to tell that can bear witness in ways that others cannot—and telling those stories is their gift to the world and their opportunity both to enrich and change the world.

James: We need to tell stories of we. That’s why I moved back to Hawai’i 20+ years ago. I wanted to tell MY stories and thru local commercials (my day job) that’s what I’ve been doing. It’s important to put a very authentic view on who we are and where we come from. This movie isn’t everyone’s story, but I hope people see a part of their life in the story, and can relate and connect to the characters. I just want people to know their stories are important and that they are important. What better way to say that but in a movie.

I hope people come see Growing Up Local and feel that they are authentically represented on film. I also hope they share their thoughts and feelings about the movie with their friends and family, and maybe this allows them talk about their lives and dreams with each other. Sharing is caring 🙂

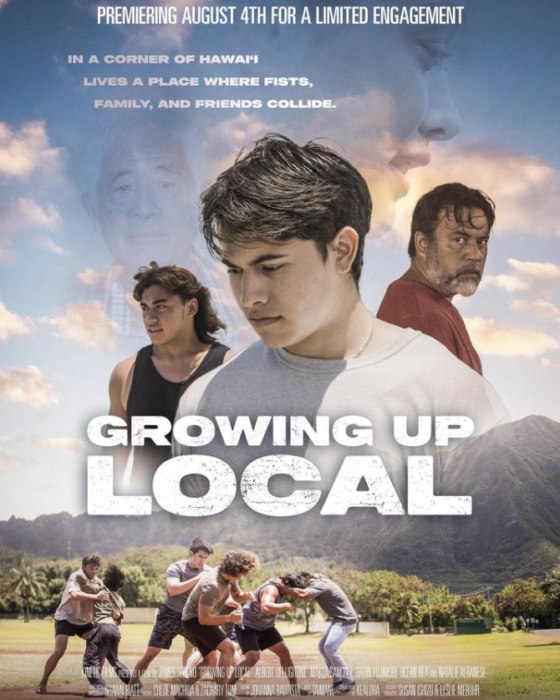

Growing Up Local (the movie) premiers next weekend, August 4-6, 2023 at two Consolidated Theater locations with various show times to choose from. Go check it out and see if you can spock some of the actual Bamboo Ridge books used in one of the scenes!

For more information or to view a trailer, visit the Growing Up Local website or Kinetic Productions, James’ production company.

BIG mahalos to Stuart Ching and James Sereno for sharing their creative journey with us!

From the film’s website:

In a place known as paradise, Stanley’s life is far from it.

Using the unexplored and often tough neighborhoods of Hawai’i as a backdrop, Growing Up Local uncovers a boy’s struggle to establish his identity beyond his father’s fists and his loyalty to his friends. The tale of Stanley explores three generations of the Nagata family, and tells the universal story of the conflict between father and a son and the expectations and burdens that are passed on from generation to generation.

Growing Up Local takes us beyond the stereotypical view of Hawai’i, and goes deeper into a world and a culture that many call home.

Growing Up Local (BR Issue #72, 1998) is the result of the combined vision of three organizations, all dedicated to the enhancement of education in Hawaiʻi: Bamboo Ridge Press, Curriculum Research and Development Group (CRDG) and Hawaiʻi Education Association (HEA).

Talk story