Of Joseph Kahahawai:

I would grieve all my life.

Though the grieving would change over the years,

the angry shark of it that attacked my gut,

lessening its hold on me in time.

But I can guarantee you one thing.

Every morning when I wake up,

it would be back at my doorstep

like the old familiar neighborhood stray cat

let in to curl at my side for the rest of the day.

And this grief would well up

at odd moments in my life.

When I see the face of a child at the window

looking out, or a boy on his bike,

cards between the spokes

making sounds in the wind.

Or, at a sudden rain, splattering

its droplets

upon the roof of my memory.

It would serve as a memento—

the stone I carry in my pocket,

the golden locket I hang around my neck.

This grief would rise up in me

when I see a rainbow or the setting sun,

or when I smell his shirt still hanging

in the closet, and, once in a while take

up to my face. Be overcome.

By his scent I would drop to my knees

and fall to the floor and slap

the hard dark wood with my hands.

While I would scold myself: "Don't do this!"

I would never stop.

I wouldn't be able to help myself,

grief the only way to be closest to him.

Of Thalia Massie:

Looking back at this mess

as an old woman,

I can tell you that my pain and

suffering never ceased,

for retribution comes one way

or another. I learned this

too late,

despite my triumphant release,

the commutation, the one-hour sentence,

I spent drinking champagne.

In triumph? Perhaps. In the end, however,

I endured a greater sentence–

a life sentence of regret and remorse

not for killing Kahahawai.

I still have a cold heart where he's concerned,

for I believe he was the perpetrator.

But the pain I felt was for my daughter

as I watched her plummet

as if from the cliffs of the Pali,

becoming an alcoholic, a drug addict,

and at the end, someone who tried

to commit suicide once, twice,

succeeding on the second try,

her body found in some cheap hotel room.

I have to admit. I shared the same

grief as Joseph Kahahawai's mother,

for I was as passionate a mother as she

where Thalia was concerned when she was brutalized.

Wasn't that the thrust of Tommie's and my

wanting to murder her son in the first place?

Thalia's suffering, my suffering,

Thalia's pain, my pain,

her death, my death.

I was heartbroken when I went to collect

her body and bury her in the cold

hard ground so far away from your angry

shores where the ripples

of outrage

continue through the years.

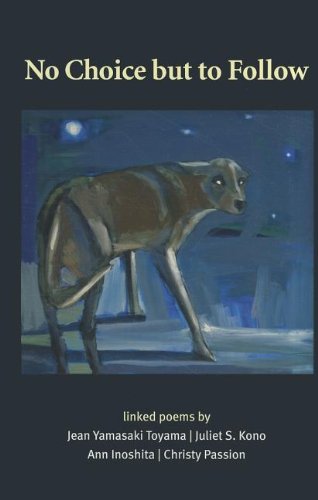

No Choice but to Follow

No Choice but to Follow