Subtotal: $13.40

Article

Pidgin perspective

A filmmaker looks at island culture through the lens of local language

By Katherine Nichols of the Starbulletin

After spending most of her adult life in Boston, filmmaker Marlene Booth began visiting the islands in 2000 and said it didn’t take long before "Hawaii got into my bones." The desire for a long-term project began to germinate, but she wondered how to encapsulate this unique culture in a film. "I was so struck by how little I’d known about Hawaii before I came here."

Yet Booth, who earned a master’s in fine arts from Yale University in 1975 and has been making award-winning films ever since, wanted to learn.

Fast-forward through several years of research and a growing friendship with the late Kanalu Young, a former professor of Hawaiian studies at the University of Hawaii. He suggested they look beyond the Hawaiian language to pidgin, because without pidgin, he told Booth, he would "cease to be whole." Under his tutelage, she realized that "pidgin really does seem to be the language of the heart."

The project began in earnest when she received a research and development grant from Pacific Islanders in Communication. When Booth’s husband, Avi Soifer, became dean of University of Hawaii’s School of Law in 2003, they moved here permanently.

Even then the story of pidgin remained elusive. Booth understood that it is a distinct yet universal language derived from many ethnicities trying to communicate with each other on plantations. But what does it mean to the people who speak it?

When Young, who became a quadriplegic in a diving accident at age 15, suffered health complications, his schedule slowed enough to allow him to share his musings about the connections between ethnic Hawaiian and pidgin.

"He had the insider’s perspective and I had the outsider’s perspective, and together we were going to find our way through this film," she said. Shooting began in 2005. Thankfully, they had just enough time before Young died last year.

"He was a remarkable guy," said Booth, who dedicated the film to Young. "What was open to him, he grabbed with intelligence and passion."

With extensive use of historical photos and interviews with Waianae and Punahou School students, as well as pidgin and linguistics experts, the film explores language and culture with enough nuance and clarity to satisfy both experts and neophytes.

In a clever and rather unexpected addition, the pidgin dialogue includes subtitles — written in pidgin instead of standard English. Booth intersperses serious interviews with entertaining minilessons that evoke the humor and creativity omnipresent in the language. She also investigates pidgin’s evolution and the role it’s played in schools, social connections and careers.

"It’s a mixed picture," she explained. For some people, speaking pidgin provides a powerful sense of identity, yet they also feel judged and ashamed — emotions that arise from pidgin’s enduring association with poor English. "So people carry this duality. There are attitudes that people bring to pidgin that they don’t even realize they’re bringing. But there’s a reason we call the language of home ‘mother tongue.’ You don’t want to, nor should you be forced to, give up your mother."

In the end, the project became Young’s gift to Booth because it opened the door to Hawaii. "It was a labor of love," she said. "I learned so much from him about how to live here

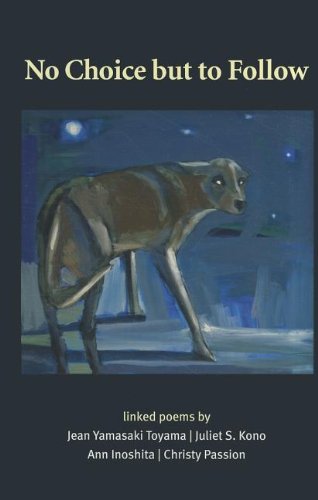

No Choice but to Follow

No Choice but to Follow

Really cool movie.

I was anxious to see the project that Marlene has been working on for so long. Apparently 400 other people wanted to see it too and I couldn’t get in the Art Auditorium. I’m sure there will be other chances to see it…it’s nice to see that pidgin NOT PAU YET!