Subtotal: $13.40

she alleged, six or seven times,

in her beautiful green dress.

I was that green dress.

Now,

I am the ghost

of that green dress.

These days,

I float ethereally

from where the Ala Wai Inn stood

and down John Ena Road

near Fort DeRussy,

where people—

Mrs. George Goeas, Alice Araki,

and Eugenio Batungbacal—

testified they saw me

pass them by,

which places me

in the area late that night.

I am the ghost of the green dress

that Thalia wore,

when she said she was abducted

by five young locals

and brought to a place–

dark, isolated, desolate–

in Ala Moana,

known as "Beach Road,"

where only a few

small fishing boats

creaked in the dark

and dogs whined, their cries

coming from the old

animal quarantine station.

I am the ghost of the dress

that weaves in and out

the psyche of Hawaii's people.

I am there when the brah on

on the street says:

"Eh haole, what you looking at?

You like beef?" Or when the local

kid cannot understand why he hates

guys in uniform and feels

like he wants to punch them out,

but will sign up

to fight with them in Iraq

because he needs a job.

He does what he does,

but can hardly wait to bug out.

I'm there when the haole looks

at the local kid "funny kine," or can't

look him in the eye because

he's not white or thinks

the kid's stupid because

he can only speak "da kine"

you know, Pidgin,

and look down on him,

as if he were low class,

uneducated, poor. Trash.

Animosity working both ways.

Unlike hospital-green frock,

I was once viridescent,

as sunlit slopes

of the Ko'olau mountains;

as the pleasure

garden sullied by the vertiginous

minds of whomever did this,

to her, my wearer.

I was viridescent as the ocean

in a green-bloom of limu,

a green that accentuated

the color of her fair skin

her light, soulful eyes

and red lips,

fine brown hair.

To have seen her,

you would have been

hard-pressed to say

she was pretty,

but unconventionally

attractive, she was taller

than most women in the islands

and had the kind of lugubrious

chic-ness made of money and unhappiness,

as she walked away from the Inn

in an inebriated sway.

In the car

where she said she was raped,

I don't remember

if I were lifted gently from her legs

or shoved up to her waist

with trembling hands

or pressed by desire

against the heaving

want and weight

of desperate men.

I don't remember if they nestled

their need into my neckline

as they drooled into her cleavage,

if they even did, indeed.

After whatever happened,

once at home,

I was taken off

and hung like a scarecrow

in her bedroom.

She called the police

to say that she'd been beaten

and raped and the detectives

came to take her statement,

but Detective Bill Furtado

and his partner George Harbottle

did not inspect me much,

hanging in her room.

Only much later was I scrutinized

whereupon they found but a tiny blood

spot and a bit of soil.

Nothing more.

I remained green.

Was clean.

I don't know when it happened,

maybe this part

folded into my imagination,

but some months later,

I was stripped from the hanger,

and stomped on, in anger.

Torn across the bodice,

I was dragged out

and taken to the backyard

where I was hung and set on fire.

Burned in effigy.

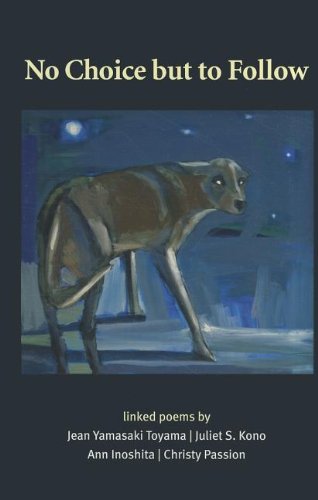

No Choice but to Follow

No Choice but to Follow

Talk story